After several months of investigation, the University of Michigan found for Jane. John was forced to withdraw from the university, just 13.5 credits shy of graduating.

But then John took a step that is becoming more common among students who believe they have been harmed by tough policies aimed at combating campus sexual assault. He hired a lawyer and took the university to court, maintaining his innocence and charging the school had denied him even the rudiments of due process, specifically the right to question or cross-examine his accuser.

And in the preliminary legal skirmishing that has taken place so far, a federal appeals court thunderously rejected the university’s motion to dismiss John’s lawsuit.

“When it comes to due process, the ‘opportunity to be heard’ is the constitutional minimum,” Judge Amul Thapar wrote in a majority decision. “If a student is accused of misconduct, the university must hold some sort of hearing before imposing a sentence as serious as expulsion or suspension, and … that hearing must include an opportunity for cross-examination.”

Two powerful currents regarding sexual misconduct are clashing on campus. One is an intensified effort to prosecute the mostly male students accused of such misconduct – sustained by an Obama administration-inspired crackdown and the more recent #MeToo movement, and fueled by press reports about an alarming frequency of unpunished sex offenses.

The counter-current is the pushback from accused students, who are hiring lawyers to argue their clients were caught up in murky sexual situations but found guilty in what to amount mock trials that resulted in severe consequences.

Exactly how many cases have been brought is hard to determine. Experts say dozens of them have been filed in state courts, where there is no central repository of information, and scores more have been settled before they were decided in the courts.

The federal courts offer a more precise number, according to research by K.C. Johnson, a historian at Brooklyn College, and Samantha Harris, a vice president at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. Since 2011, 142 lawsuits by accused men have been brought in federal courts on which substantive rulings have been made, often regarding whether to dismiss or to allow the proceeding to move forward. Judges have found the universities at fault in more than half the cases, 77, while one produced a mixed result. The legal reasons were varied, including a failure to provide due process – that is, university disciplinary boards did not allow accused men open, fair hearings with an opportunity to cross-examine their accusers. In other cases, universities have been found in violation of their own rules and procedures.

In an ironic twist, judges have found in some cases that schools’ procedures were so weighted against accused men that their rights were violated under Title IX, the section of the Civil Rights Act that prohibits sexual discrimination. Title IX was devised mainly to protect women against discrimination; now at least some courts have ruled that the tendency of universities automatically to “believe women” amounts to gender discrimination against men.

The “sex police” at universities “are being hammered by an unprecedented wave of litigation, and higher education is losing,” according to a white paper by the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management, a for-profit consulting company. “If you are the sex police, your overzealousness to impose sexual correctness is causing a backlash that is going to set back the entire consent movement.”

The wave of lawsuits also is an unintended consequence of the Obama administration’s efforts to respond to loud and widespread complaints that little was being done to address an “epidemic” of sexual assault on campus.

In 2011, the Department of Education’s Civil Rights Division sent a “Dear Colleague” letter to more than 7,000 colleges and universities that receive federal funding. The letter advised them to lower the standard of proof required to find a student guilty of a sexual offense from the “clear and convincing” standard commonly in use, to a “preponderance of the evidence” standard, meaning that an accusation need only be “more likely [true] than not” for an accused person to be found guilty.

The letter warned that the failure to adopt these guidelines could result in a Title IX violation, putting federal grants at risk. Noncompliance could also open schools to prosecution by the Department of Justice, and, in fact, the DOJ did open investigations of several dozen schools, including some that have been the targets of lawsuits by accused men.

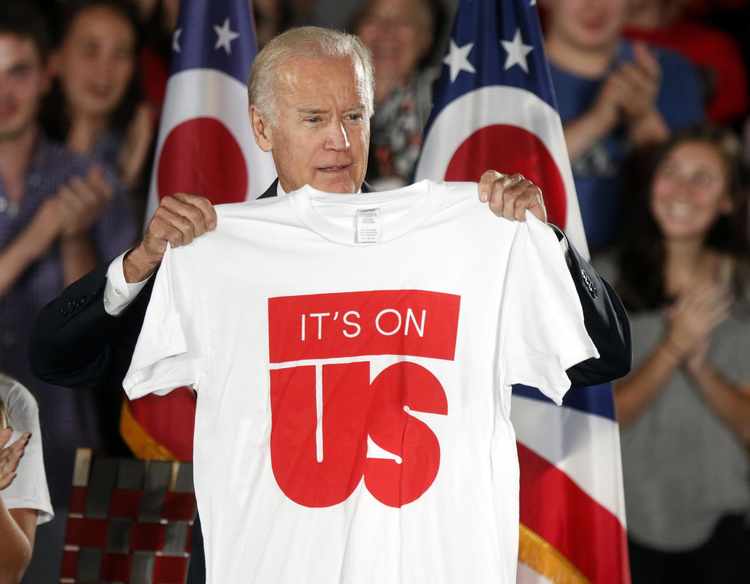

The Obama guidelines were embraced by women’s groups and schools alike as a welcome effort, at last, to combat sexual assault. There were rallies on many campuses, anti-sexual violence campaigns such as “Start by Believing” and “It’s on Us.” Prominent figures, including Vice President Joe Biden, appeared at universities and endorsed these campaigns, as did many university chancellors and presidents. For example, at the University of Michigan, John Doe’s and Jane Roe’s school, President Mark Schlissel signed a “Start by Believing Proclamation” as part of a “National Sexual Assault Awareness Month.” This “ ‘flips the script’ on the message victims have historically received from professions and support people,” the movement’s websitesays, “which is ‘How do I know you’re not lying?’ ”

Meanwhile, new administrators were hired and procedures put in place to handle charges of sexual assault. The guidelines often encouraged review boards and investigators charged with looking into such allegations not to hold open hearings or to allow cross-examinations of female accusers for fear of humiliating or re-traumatizing them.

The problem is that the vast majority of accusations of sexual misconduct, like the one at the University of Michigan, involved behavior that was witnessed only by two people, the accuser and the accused. In most cases the two parties were under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time, and each had different versions of what took place. If the accuser is assumed to be telling the truth, the accused must be assumed to be lying, which is at odds with the concept of the presumption of innocence.

These circumstances are at the heart of the legal backlash driven by accused students who claim their schools rushed to judgment against them, violating their rights as they did so, to satisfy demands for aggressive action against sexual violence.

The backlash could gain some support from Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’s move last year to rescind the Obama guidelines and allow schools to return to “clear and convincing evidence” as the standard of proof. So far, few schools seem interested in changing policies. And there doesn’t seem to be a vigorous national effort to reform the system.

As a result, pushback is happening on a case-by-case basis, and it isn’t going away. “I’m getting as many calls as ever,” said Andrew Miltenberg, a Manhattan attorney who has sued some two dozen universities over the past few years on behalf of male students.

The backlash is not surprising, given the stakes. “These guys find themselves expelled,” said Deborah L. Gordon, a Michigan civil rights lawyer who represented John Doe in his suit. For a young man to be expelled from a university, moreover, means not getting a degree, losing the tuition he’s already paid, and having the label of sexual offender placed on his permanent record. “So, gradually these cases have been making their way through the courts,” Gordon said, “which have mainly been affirming the due process rights of the accused.”

Miltenberg himself came to public attention a couple of years ago when he invoked Title IX to sue Columbia University on behalf of Paul Nungesser, who was accused of rape by a fellow student and cleared by the school. Nungesser argued that the school discriminated against him because it allowed his accuser to carry a mattress around campus for a year to protest the university’s decision not to prosecute the case. Miltenberg won a confidential settlement for his client in that case.

After that, Miltenberg filed a suit against Vassar College for a Chinese student he believed was falsely accused of sexual misconduct. Miltenberg lost that case, but gained attention. “People started calling from left and right,” he said. “There was an underground culture of parents whose kids had gone through this.” Recently his firm opened an office in Boston to be in an area thick with colleges and universities.

Miltenberg said schools have been ill equipped – both structurally and ideologically – to deal with sexual abuse cases. “In 2011 and 2012, when the Dear Colleague Letter came down, most universities didn’t have Title IX coordinators,” he said. “Most conduct review boards were set up for things like plagiarism, cheating, or throwing a lamp while under the influence.

“When the universities saw the uproar about sexual assault,” he continued, “what did they do? Did they hire retired FBI agents or police detectives to carry out Title IX investigations? No. They turned to people whose backgrounds are either in victim rights, or domestic violence, or they’re women’s rights advocates, people who have led campaigns to be tougher on sexual assaults. These are not the people who should be investigating and adjudicating these matters.”

Miltenberg’s recent filing against the University of Colorado, Boulder, contains the basic elements of many of his cases. A freshman from Italy, Girolamo Francesco Messeri, and a male friend met two girls one night, neither of whom were students at the college. The four ended up in the boy’s dorm room, where Messeri and one of the women began making out. For less than five minutes, the pair went into the bathroom where, according to Miltenberg’s complaint, she performed oral sex on Messeri.

Two days later, the woman went to the campus police and accused him of a forced sexual encounter. On that same day, according to Miltenberg, Messeri was expelled from his dormitory and forced to live in a hotel, on the ground that he posed a danger on campus. Two months after that, a pair of investigators for the Office of Institutional Equity and Compliance issued a “finding” that Messeri was responsible for “sexual assault.”

But according to Miltenberg, the investigators did not hold a hearing and never even interviewed the accuser, relying instead on interviews conducted by the campus police.

Messeri’s friend testified that the female student seemed unruffled and unbothered when she emerged from the bathroom; she also, the complaint says, continued to spend time with Messeri, later went to a party, smoked marijuana, and mugged for the camera as she took selfies with her friend. But the university investigators gave credence only to the friend of the accuser, who supported her allegation. Later, the criminal case against Messeri was dismissed on the recommendation of the Boulder district attorney. In the meantime, however, the university’s Title IX coordinator, Valerie Simons, informed Messeri that he was being expelled.

“CU-Boulder’s investigation and adjudication of Jane Roe’s allegations were tainted by gender bias resulting from federal and local pressure to protect female victims of sexual violence,” Miltenberg’s complaint reads. “… As a result, Plaintiff was deprived of a fair and impartial hearing with adequate due process protections, as mandated by the United States Constitution.”

A CU-Boulder spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

The case against CU-Boulder has yet to be heard in court, but in a large number of similar cases, the courts have been sympathetic to the due process complaint. According to the tabulation made by Johnson and Harris, since 2011 the federal courts have allowed 21 cases claiming due process violations to proceed following university attempts to have them dismissed.

An example was a case brought against Ohio State University. In November 2014, Jane Roe, a female medical student there, accused a fellow student of sexually assaulting her during an encounter that had occurred 10 months earlier. Jane said that she had been too drunk to be able to give her consent, which was a violation of the university’s code of conduct. John Doe claimed that Jane, with whom he had had sexual relations for over a year, was alert and talkative during the encounter and that the sex was consensual.

A university Conduct Board Hearing sided with Jane, and John was expelled before he could complete his fourth and final year of medical school. He was also forced to leave his job as a registered nurse at the university’s Wexner Medical Center.

But there were some odd aspects of the case seemingly ignored by the university. Most important, it turned out that Jane filed her complaint a few days after she had received a notice from the university that she would have to withdraw because of failing grades. This decision, however, was rescinded when she told a review committee that her poor academic performance was due to the sexual assault she had suffered. In other words, it would seem that Jane might have had a motive to fabricate a charge of sexual assault. John, however, had been informed of none of this, the court found, and it was therefore impossible for him to “effectively cross-examine Jane Roe on a critical issue: her credibility, and specifically, her motive to lie.”

In rejecting the university’s motion to dismiss John’s suit, the court said that “universities perhaps, in their zeal to end the scourge of campus sexual assaults, turned a blind eye to the rights of accused students. Put another way, the snake might be eating its own tail.”

Lack of due process is one way courts have decided for plaintiffs, but there are other ways as well. In 26 cases, according to Johnson and Harris, courts have found universities in breach of contract, meaning a failure to follow their own published procedures, or procedures that were inherently inequitable.

In a 2017 suit against the University of Notre Dame, a judge barred the school from taking action, pending a full hearing, against a student being expelled after being accused by an ex-girlfriend. The judge in the case found that the university’s procedures were “arbitrary and capricious in a number of respects,” among them a refusal by the school’s hearing panel to consider text messages and phone recordings that, in the judge’s words, “seriously undermined Jane’s testimony at the hearing.”

What about the considerable number of cases, 64, that have gone in favor of universities? In seven of them, lower court rulings favorable to universities seemed to have been undermined by later appeals court rulings, but had not been formally reversed. In 18, rulings were made on some grounds other than the actual merits — for example, that the accused student wasn’t able to show that enough harm had been done to him to justify going to court. In another 23 rulings, courts found that they should not be overruled even despite procedural flaws, since the school’s findings against the accused seemed accurate. In only sixteen of the cases did judges rule in favor of the universities after the accused student raised serious questions about the guilty finding against him and the fairness of the process.

In a suit brought against Purdue University, for example, a judge found that the male plaintiff had no “property interest” in his education at Purdue, and therefore the due process protections of the 14th Amendment didn’t apply.

Still, the number of cases that have gone favorably for them has led some lawyers and analysts to believe that new case law is being made, especially in reaffirming the legal necessity for men facing expulsion to have the right, at the very least, to question the women accusing them.

But Miltenberg is cautious. “We have achieved some very good results, and progress towards transparency, equity and due process are being made,” he said. “But there is still a long road ahead until we can have confidence in the campus disciplinary process and the manner in which courts are interpreting Title IX.”